In-depth: ClickHouse vs Elasticsearch

Mar 20, 2023

- Mathew Pregasen

Elasticsearch and ClickHouse are both open-source frameworks with advantages over conventional databases like PostgreSQL for performing tasks over lots of data, but they serve very different needs.

Elasticsearch, as the name implies, was designed to power better search. It can efficiently return search results, such as grocery items on a grocer’s website, accounting for things such as spelling mistakes. It's the bedrock product for Elastic, which sells Elastic Cloud – a managed solution that bundles Elasticsearch with other data products.

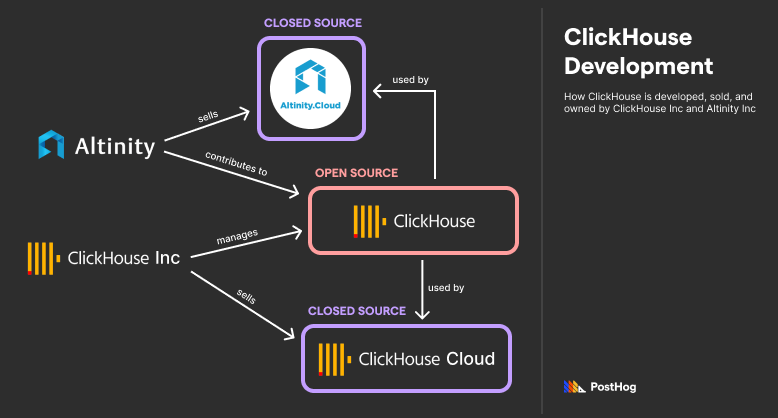

ClickHouse, meanwhile, excels at aggregating data for uses like business analytics or financial statistics. While the database, ClickHouse, remains open source, it is managed by the for-profit ClickHouse Inc. ClickHouse Inc.’s main offering is ClickHouse Cloud, a managed service similar to Elastic Cloud, just for deploying ClickHouse instead. However, ClickHouse also merges notable contributions by Altinity, a separate company that sells Altinity.Cloud, a managed service for deploying ClickHouse in Kubernetes.

Elasticsearch and ClickHouse are interesting to compare because of their vastly different architecture, optimized for each of their respective goals. Comparing them is a good meditation on how physical and virtual layouts can improve efficiency toward a specific efficiency goal.

Background

Sometimes, the relationship between an open-source tool and its lead developer is complicated. ClickHouse's relationship is straightforward, but Elastic has a complex history with open source.

What is Elasticsearch?

Elasticsearch was originally released in 2010 under an open-source license. The premise behind Elasticsearch was that Apache Lucene, an open-source product designed to efficiently search JSON documents, needed better infrastructure for scaling. Apache Lucene made it easy to organize and search a series of JSON documents – such as human profiles; Elasticsearch made it easy to distribute those human profiles, which might be in the billions, across multiple locations, indexed both physically and virtually.

Elasticsearch is considered a NoSQL database because it uses Apache Lucene – and by extension, JSON documents – as a primary store of data. Specifically, it is a Document-Store NoSQL database with a focus on searching and retrieving data. It is never used as the primary store of data. Elasticsearch data stores are often redundantly available in a more traditional database like PostgreSQL as Elasticsearch is only leveraged to improve search results.

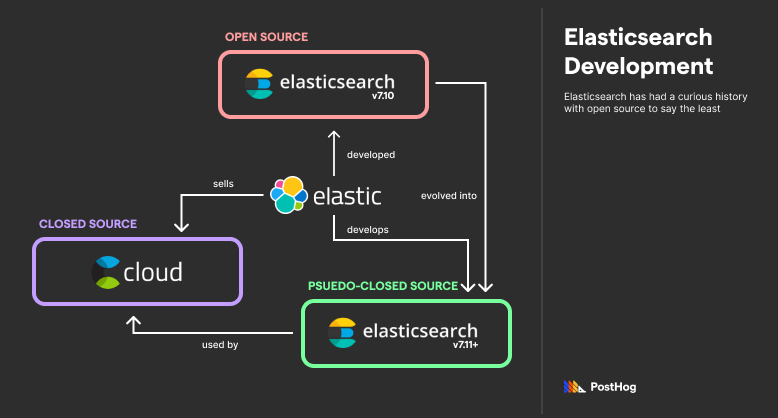

In 2021, Elasticsearch abandoned its traditional Apache Open Source license in favor of a new license known as an Elastic license. It was a controversial move motivated by Elastic’s irritation with Amazon profiting off of Elasticsearch by operating a managed service without ever contributing to the codebase. Amazon forked the last version of open-source Elasticsearch into a new open-source project, OpenSearch. Similar to Elastic (and ClickHouse Inc.), Amazon launched a managed version of OpenSearch.

Elasticsearch’s new license allows developers to implement Elasticsearch themselves, but forbids cloud distributors from running a for-profit, managed Elasticsearch service. Most open-source advocates consider Elastic’s Elastic License not open-source; however, it would be unfair to Elastic to equate their solution’s transparency with a purely closed-source solution like Snowflake.

Elastic also develops Kibana, a visualization program that plugs into Elasticsearch. It was also developed under an open-source license then shifted to an Elastic License in 2021. Kibana provides an interface for designing a dashboard that showcases Elasticsearch data.

What is Clickhouse?

ClickHouse is a traditional open-source project, but it started as a proprietary application. ClickHouse was originally built by Yandex for Yandex.Metrica, a massive analytics tool popular in Russia. Eventually, ClickHouse spun out into an independent, open-source project. Today, it is managed by ClickHouse Inc. with notable contributions by a separate organization, Altinity Inc.

ClickHouse was designed to return aggregate values of big data at millisecond speeds. ClickHouse accomplishes this through a series of clever techniques, including using a columnar store, dynamic materialized views, and specialized engines that take advantage of multiple cores.

Similar to Elastic Cloud, ClickHouse can be (optionally) deployed through various managed, closed-source solutions. ClickHouse Inc. offers a managed service known as ClickHouse Cloud. ClickHouse Cloud includes a GUI, similar to Kibana, for querying and visualizing data. Separately, Altinity Inc offers a managed service known as Altinity Cloud that specializes in deploying ClickHouse on Kubernetes.

Data and infrastructure

The biggest, defining difference between Elasticsearch and ClickHouse is their respective techniques for storing and organizing data.

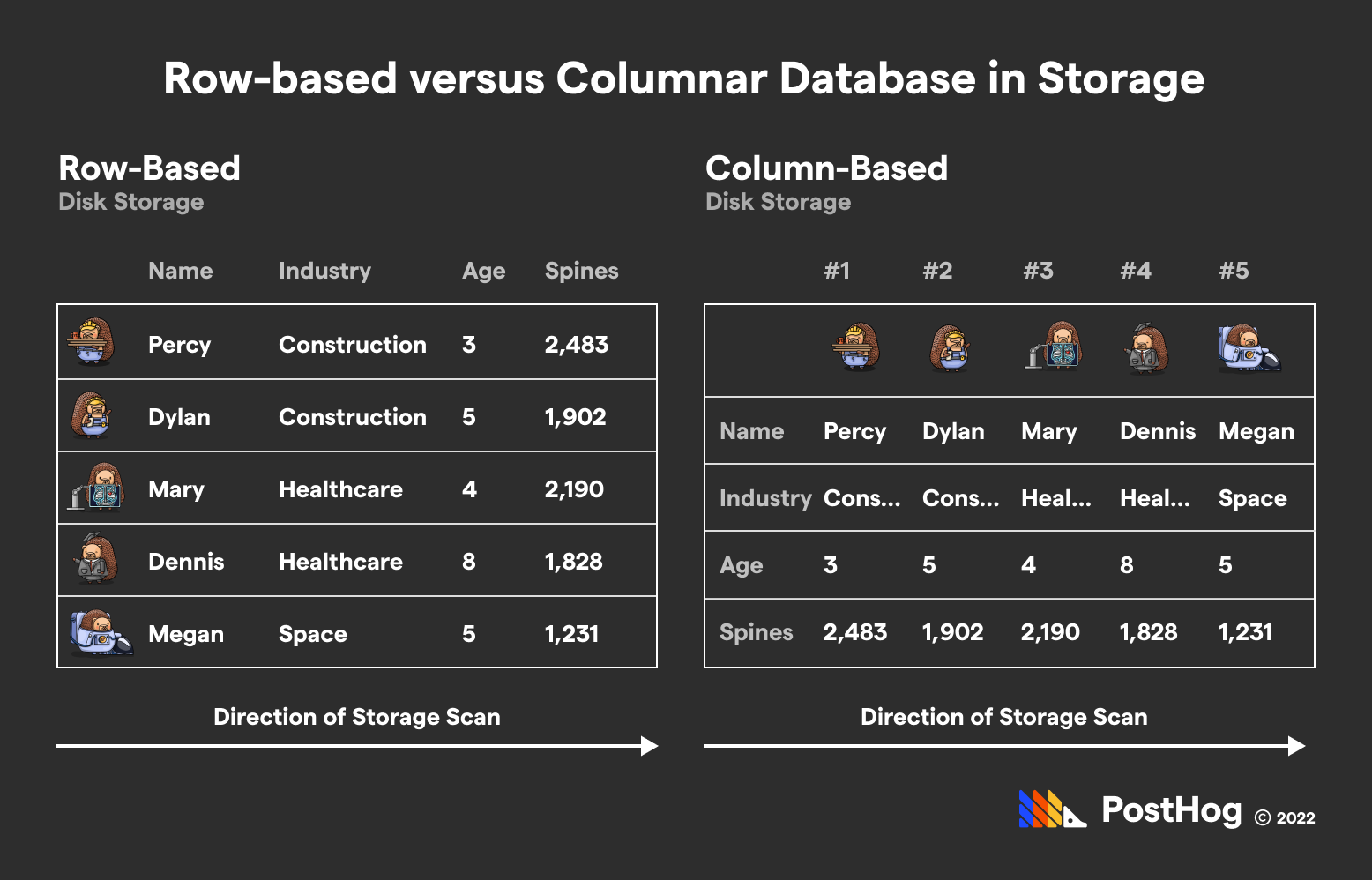

ClickHouse is a columnar database; it stores data in a table, just with an inverted structure (in disk) relative to a traditional MySQL or PostgreSQL table. ClickHouse’s columnar data store simplifies aggregating data.

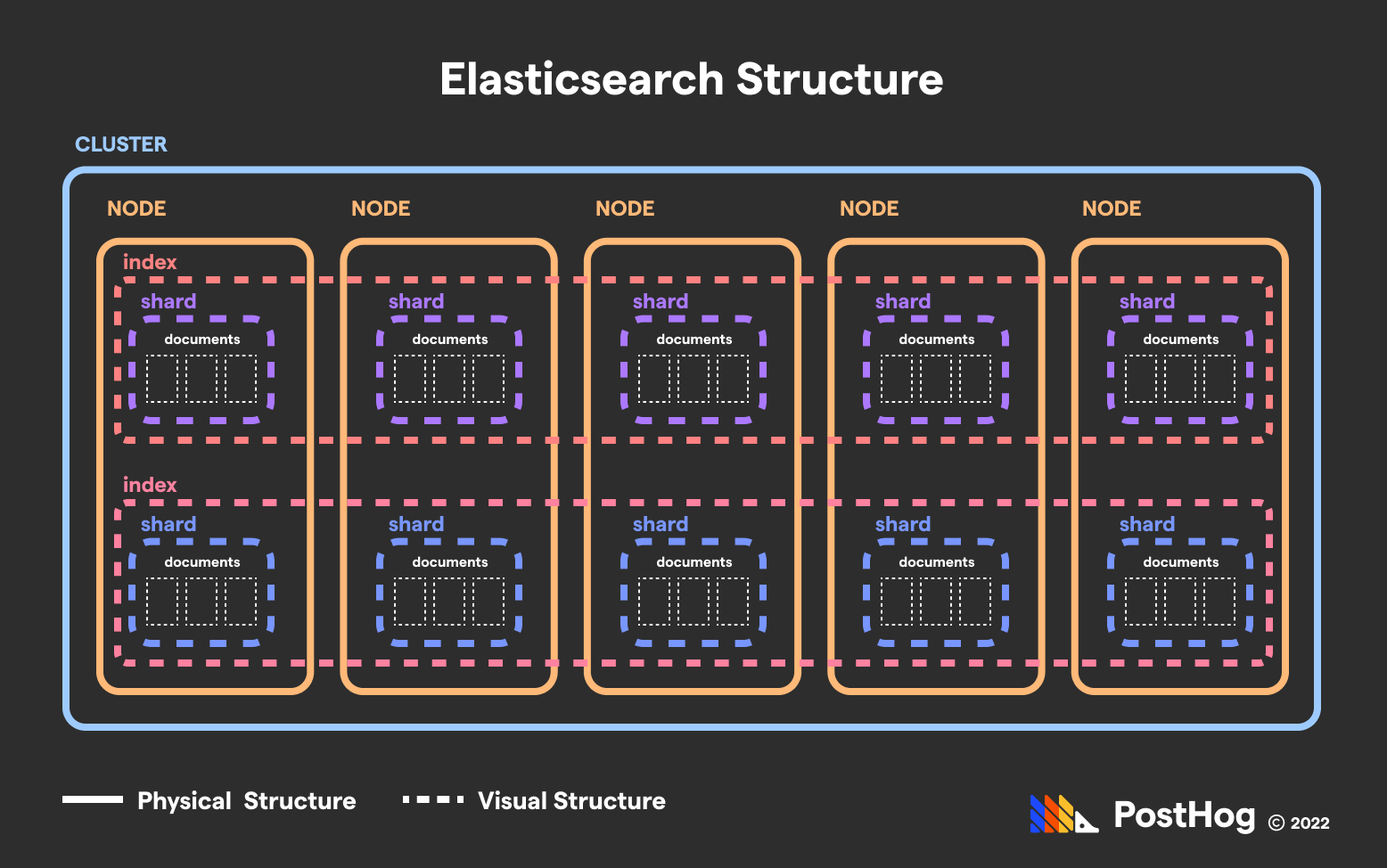

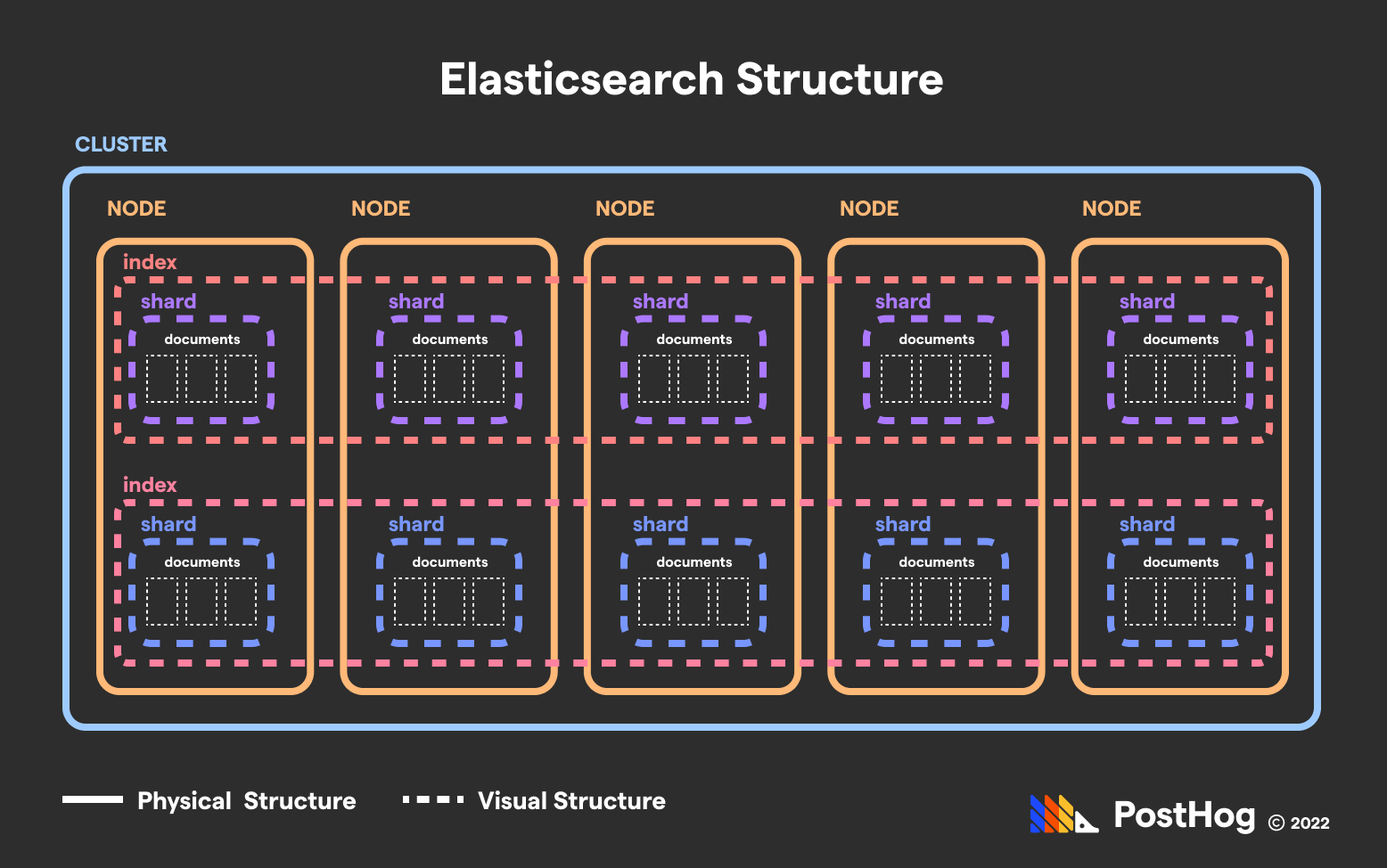

Elasticsearch isn’t columnar – it isn’t even a table-based database. It stores data as documents, grouping sets of documents into shards, which are part of physical and virtual collections respectively known as nodes and indices.

Elasticsearch’s structure explained

Elasticsearch is best understood by separating the virtual structures from the physical structures.

Documents (virtual)

A base item in Elasticsearch is known as a Document. A Document is akin to a row of table data in MySQL – it has attributes, known as fields, stored in a JSON schema.

An Elasticsearch document might look something like this:

Fields (virtual)

A field is an attribute of a document. In the previous example, the fields were accountname, balance, and email. Fields make it easy for documents to be indexed and retrieved. Obviously, they also are used to store the data that applications use and present to users.

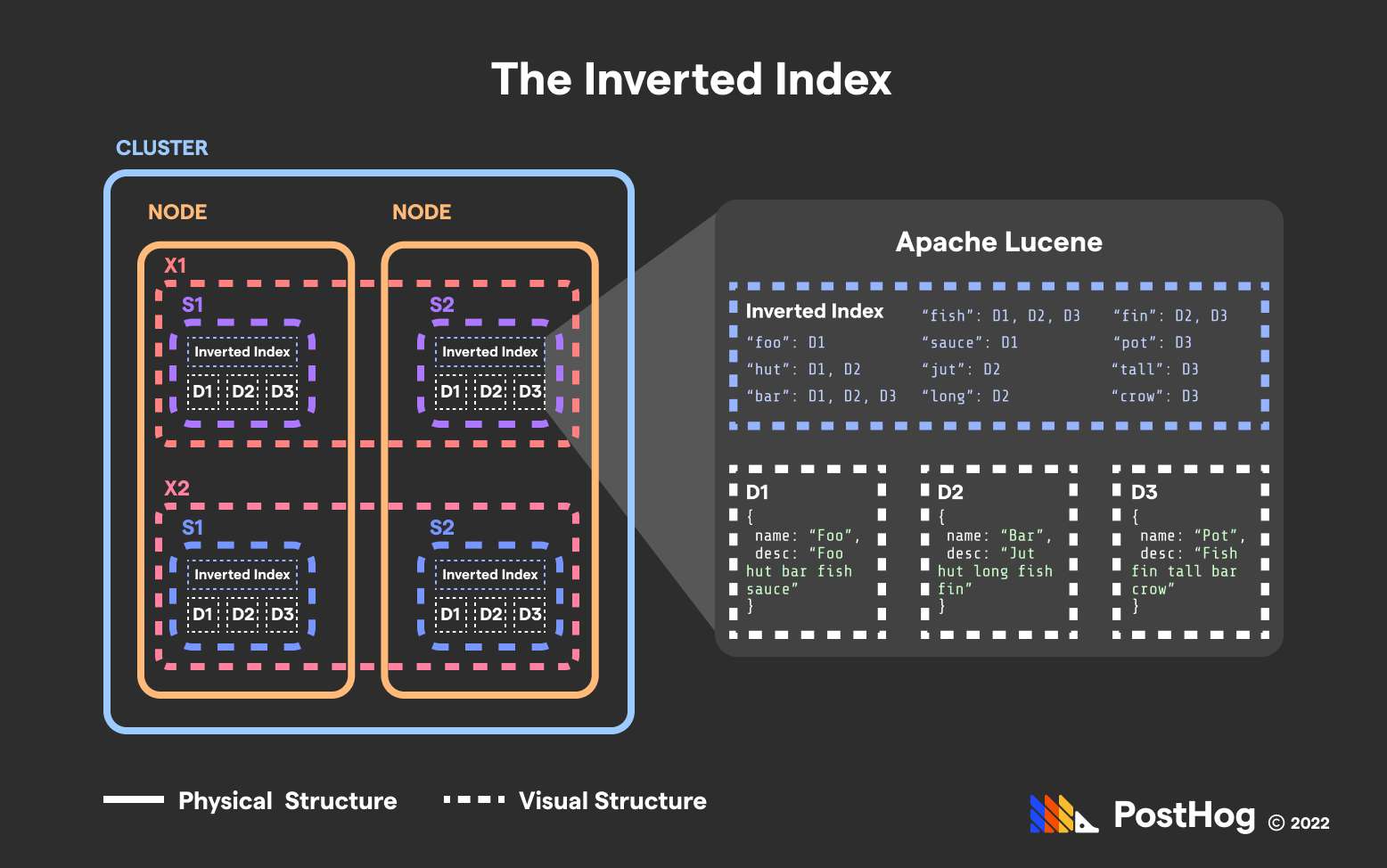

Indices (virtual), nodes (physical), and shards (virtual)

The three major core components of Elasticsearch’s infrastructure are indices, nodes, and shards. A document in Elasticsearch is part of two discrete collections:

A node, a physical machine that stores the data. Akin to a physical MySQL server, such as a device sitting in an Idaho data center.

An index, a virtual collection that defines what type of data it is. Akin to a table in MySQL, like a collection of bank accounts, student profiles, or property listings.

A shard, meanwhile, is the intersection of a specific node and a specific index. A shard is also a single instance of Apache Lucene. It is a collection of documents, such as two hundred user profiles of a total set of forty thousand.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Helping engineers and founders flex their product muscles

We'll share your email with Substack

Inverted index

In each shard (or Apache Lucene instance) is an inverted index. An inverted index is like a glossary – it stores a map of string components (such as words, numbers, or prefixes) for all the documents they are located in.

Inverted indexes dramatically speed up most queries. If a user queries for all the Reviews that use the word “outstanding”, Elasticsearch can return that collection extraordinarily fast because each shard in the Reviews index leverages an inverted index to find relevant Reviews, and Elasticsearch bundles Reviews into a single collection for the end user.

Inverted indices do not only index words and numbers, but derivatives of words. This helps with accounting for human error. For instance, Elasticsearch (or rather, Apache Lucene) will convert each word into its phonetical form and store that in an inverted index as well. That way, users can find documents with “bear” spelled “bare” with a single query.

Likewise, Elasticsearch stores prefixes, suffixes, and n-grams. And, given each word is also stored in an inverted index, Elasticsearch can leverage simple word-likeness algorithms like Levenshtein Distance to account for typos.

In short, Elasticsearch extended Apache Lucene’s inverted index into a scalable, distributed system that leverages its benefits via parallelization.

Distributed Search

This split between a virtual and physical index is what makes Elasticsearch’s ultra-fast search possible. Because Elasticsearch can perform parallel queries across nodes, multiple nodes slice and dice the search time to find a specific document.

For instance, imagine 100,000 documents stored in a single, consolidated index at 1 node. If Elasticsearch took approximately 1 second to search 10,000 documents, then searching 100,000 documents would take ~10 seconds.

Now imagine 100,000 Documents sharded across 10 nodes with 10,000 documents each. Because each node would take ~1 second to search all of the documents in its shard, and this process is parallelized, Elasticsearch can cut the search time from ~10 seconds to ~1 second.

Simply, “divide and conquer” is Elasticsearch’s middle name and trademark feature.

Replica Shards

Elasticsearch nodes and shards aren’t just used to distribute data, but also replicate it.

Elasticsearch has two types of shards – primary shards and replica shards. Replica shards are an exact copy of a primary shard should a primary shard become unavailable. A primary shard and a respective replica shard reference the same set of data. Therefore, they should never be located on the same node.

Replica shards help database operations in two distinct ways:

They protect users against data loss in case a node – which is a physical machine – fails.

Replicas are actively used for querying, so if multiple queries are targeting the same data, replica nodes can help distribute the reads, expediting results.

Clusters

A cluster is a group of nodes. Many applications only have one cluster, though some may have multiple clusters spread over different geographies to serve clients with lower latency. Each Elasticsearch cluster has a single master node that helps delegate and manage other nodes.

Clickhouse’s structure explained

ClickHouse is engineered to process data in a massive, consolidated place. Unlike Elasticsearch, ClickHouse’s optimizations don’t happen through distributing data, but by efficiently pre-processing it in anticipation of queries.

There are three major components that enable ClickHouse to return aggregations, such as averages, sums, and standard deviations, in millisecond times over petabytes of data.

Component 1: Columnar layout

ClickHouse’s columnar layout – which flips rows and columns in storage relative to a MySQL database – makes aggregations efficient.

When databases physically access data, they scan data row-by-row. By extension, if an analyst is trying to calculate the average value of bank account balances in a PostgreSQL database, they would need to access every bank account row. Alone, that would probably blow out memory. But in ClickHouse, the same analyst would only need to access one (physical) row of data – the bank balance one – and collapse it into an average.

Again, this is a physical row of data. As far as ClickHouse’s interface goes, data is still stored in a traditional format. ClickHouse’s syntax still treats individual entries as rows and attributes as columns. But under the hood, ClickHouse stores the data in an inverted arrangement, optimized for merging attribute data into single values.

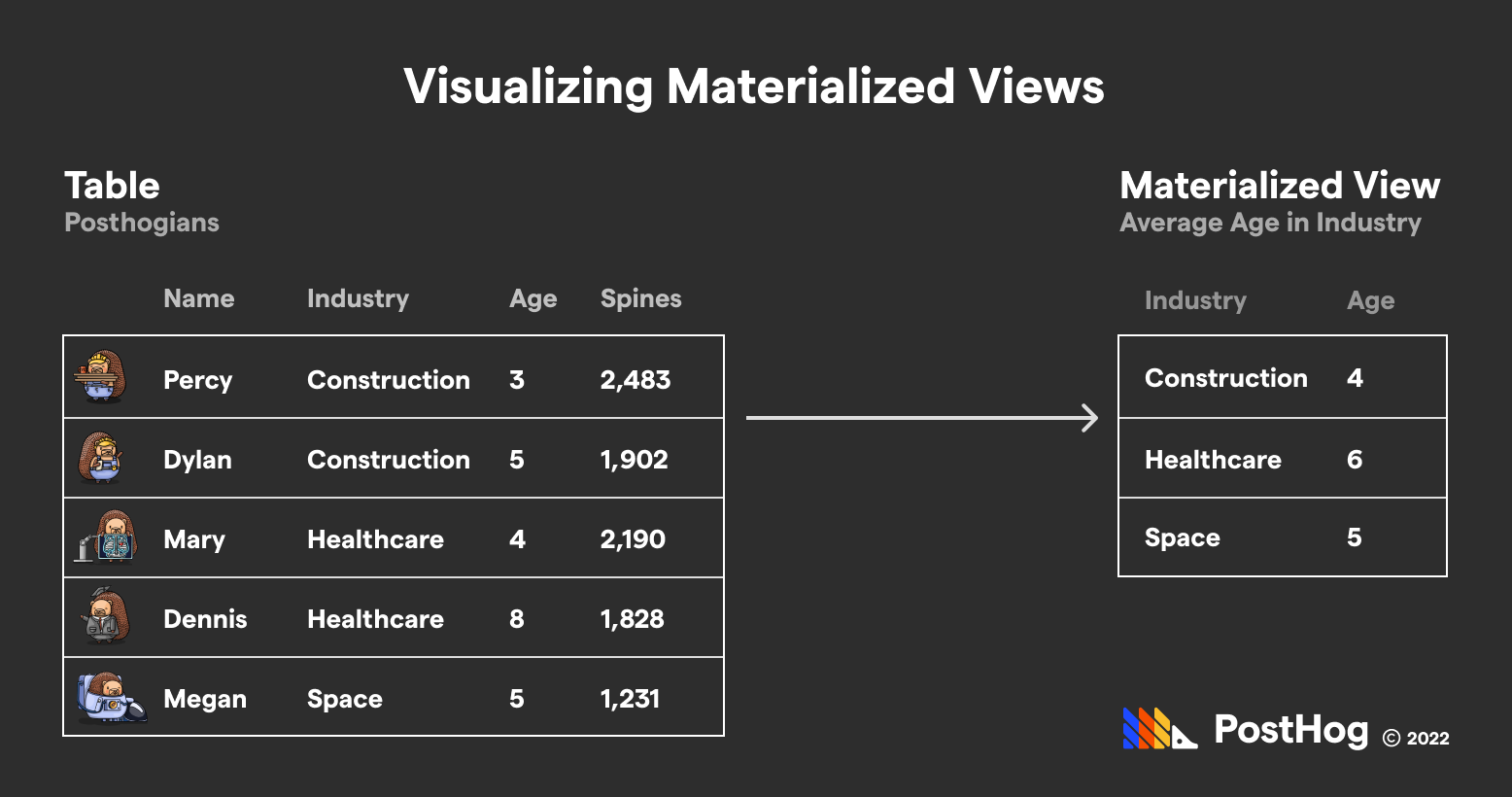

Component 2: Materialized views

ClickHouse’s second superpower is dynamic materialized views.

Materialized views are not a new concept – in MySQL or PostgreSQL, a materialized view is a new table that can be queried from, rendered by a SQL query accessing other tables. However, once new data is added to the core tables, that materialized view goes out-of-date. Because creating materialized views is often expensive in traditional databases given their non-columnar layout, refreshing materialized views can only happen occasionally.

But ClickHouse truly makes materialized views dynamic. ClickHouse doesn’t only accomplish this because of the columnar layout of its data. It also leverages incremental data structures that merges data strategically.

Component 3: Specialized engines

ClickHouse has a series of specialized engines that enable developers to take advantage of multiple CPUs in parallel on the same machine. For instance, there is an engine for summing data (SummingMergeTree) and removing duplicates (ReplacingMergeTree). This technique has some resemblance to Elasticsearch’s parallelization across multiple machines to expedite search; ClickHouse is does it at a more granular, per-machine level.

Sharding

ClickHouse has some overlap with Elasticsearch’s sharding features. ClickHouse extends Apache Zookeeper to manage multiple instances of ClickHouse should data need to be split across machines. However, this concept of sharding is closer to Elasticsearch’s support for multiple clusters – it is more a big data distribution problem, not a smaller optimization for speeding up queries.

Architecture summary

At a high level, ClickHouse and Elasticsearch’s differences showcase how they are designed to fit their own purposes. ClickHouse consolidates data so it can constantly update materialized views to serve number-hungry queries. Meanwhile, Elasticsearch is designed to find specific items, treating search queries as a group project where every node does its part.

While ClickHouse supports multiple instances, managed by Apache Zookeeper, it does not offer a decentralized solution competitive with Elasticsearch’s model. Likewise, while Elasticsearch offers data frames analytics, which has some overlap with ClickHouse’s materialized views, it is either more expensive or not as dynamic as ClickHouse’s fine-tuned aggregation machine.

Who uses ClickHouse and Elasticsearch?

Elasticsearch and ClickHouse both have small, medium, and enterprise customers.

Elasticsearch’s customers utilize it to return a specific chunk of data quickly to users. For instance, Uber uses Elastic to return data relevant to calculating surge pricing on a minute-by-minute basis. Tinder uses Elastic to fetch potential matches that might fit a user’s profile. T-Mobile uses Elasticsearch to delivery specific user profiles to customer support reps to promote better NPS scores.

In all of these examples, Elastic fetches something specific very efficiently.

Conversely, ClickHouse is used to return aggregations of data. The most obvious example would be us. We use ClickHouse to power PostHog, an open-source analytics suite that involves hundreds of aggregate values. Previously, Posthog was powered by PostgreSQL, which quickly spiraled out of control as we grew.

Others, like us, also use ClickHouse to power user-facing features – Rokt, an e-commerce platform, uses ClickHouse to power its analytics panels. However, some companies leverage ClickHouse for internal use cases, such as the Washington Post, which uses ClickHouse to power its in-house analytics suite.

Analytics performance comparison

ClickHouse was built to perform aggregations, but it’s naive to say that Elasticsearch doesn’t have the structure to compete with ClickHouse on some aggregations.

To understand this, remember the primary philosophy behind ClickHouse’s design: pre-calculate aggregations ahead of queries to enable millisecond-level fetches. ClickHouse accomplishes this through materialized views and specialized engines, which are optimized for mathematical queries transversing numeric data.

Elasticsearch, meanwhile, can accomplish similar performance over certain queries. For instance, if a product needs the number of college alumni that are unemployed, Elasticsearch can add up indices in the inverted index of words that pattern-match to unemployed alumni. In other words, fast search sometimes equates to great analytics by just adding a COUNT() function.

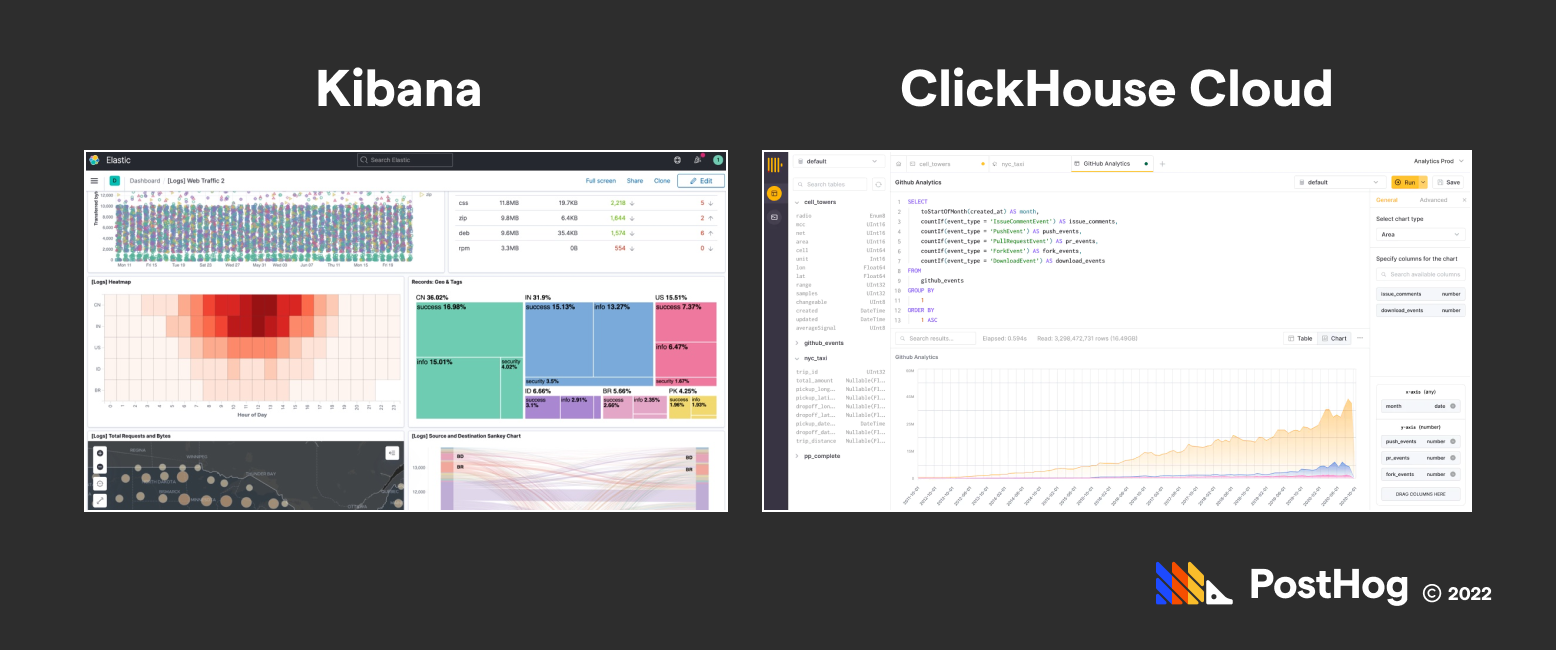

While both Elasticsearch and ClickHouse are fundamentally backend products, we can compare their respective GUI products – Kibana for Elasticsearch and ClickHouse Cloud for ClickHouse. ClickHouse Cloud is a much younger product; Kibana, conversely, has been around for nearly a decade and has an extensive UI.

In a nutshell, comparing the analytics efficiency of ClickHouse and Elasticsearch has the same sort-of, not-really awkwardness of other comparisons – they both excel in their respective categories using radically different methods to cater to a different type of need. However, Elastic’s Kibana product is more mature than ClickHouse Cloud’s competitive offering.

Final thoughts

ClickHouse and Elasticsearch are both fantastic solutions for data aggregation and fast search respectively.

Elasticsearch grew quickly thanks to fast-paced development by its parent company, Elastic. Elastic has spearheaded the development of Elasticsearch, Kibana, and other accessory products like Beats, a data shipper. For many enterprise customers, Elastic being a pseudo-closed-source solution is balanced by the fact that it can leverage its enterprise revenue to foster a massive engineering effort to improve Elastic.

Conversely, while the team behind ClickHouse is smaller, ClickHouse has an avid developer community, with contributors existing outside of the two major ClickHouse developers – ClickHouse Inc and Altinity Inc. And one of the reasons that ClickHouse is starting to grow in the last few years is because of its open-source, pro-community brand, and it's blistering performance.

Overall, Elasticsearch remains a good solution if data aggregation involves searching text. It is a more mature project with an entire suite dedicated to interfacing with Elasticsearch data. However, it is no longer a true open-source product like ClickHouse is, and isn't designed to support the kind of high-performance use cases ClickHouse excels in.

Further reading

- Lisa Jung’s talk on Elasticsearch

- Robert Hodges’s CMU talk on ClickHouse

- Our comparison of between ClickHouse and Postgres which expands on ClickHouse’s optimizations

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Helping engineers and founders flex their product muscles

We'll share your email with Substack